Session 3.3. Actions during an epidemic

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- Explain the actions that need to be taken during the epidemic phase.

- Discuss social mobilization and behaviour change communication.

- Define the roles of different actors.

Part 3.3.1. Actions during the epidemic response

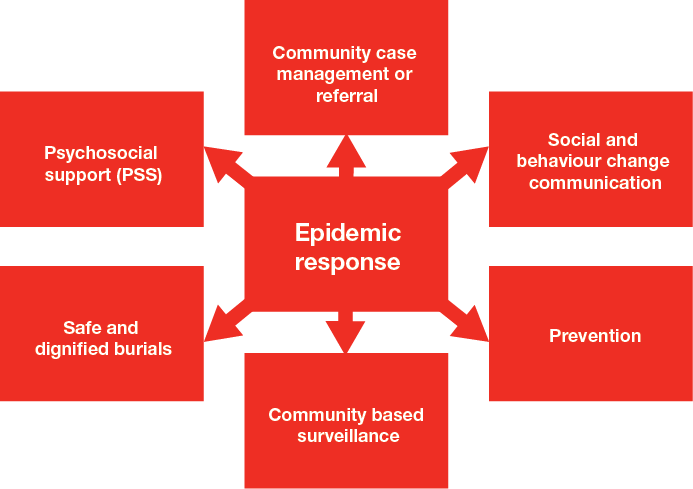

The most common activities volunteers do in response to an epidemic are set out in the diagram below.

Figure 9. Actions in the epidemic response

Social mobilization, behaviour change communication and community engagement (SBCC)

Includes activities you do to involve and listen to community members to help them to take action to protect themselves, reduce risks and prevent diseases from affecting them and spreading to others.

Prevention is any activity you do to prevent the disease from spreading. For example, it includes giving out mosquito nets, providing clean water, or supporting vaccination campaigns. These activities may help the whole community or a specific group.

Community-based surveillance is a system for detecting new cases of disease in the community and referring them to health facilities. It includes the organized collection, analysis and interpretation of data so that new cases and new potential outbreaks can be detected quickly and monitored.

Safe and dignified burial (SDB). As noted earlier, in certain epidemics (of Ebola, Marburg fever, or plague, for instance) National Societies may be asked to conduct SDBs as a public health control measure. SDBs safely bury people who have died from highly contagious diseases that have the potential to spread disease through dead bodies. Conducting SDBs requires specific training and clear protocols need to be in place.

Psychosocial support (PSS) includes activities that help members of a community to cope better with an epidemic and its effects. It manages fears and the stigma that epidemics may trigger in the community.

Community case management and referral covers the help you give to individuals who are sick. It includes, for example, providing oral rehydration solution (ORS), referring sick people to hospital, or managing a child’s fever.

Participate

Before going further, tell your facilitator what you think volunteers should do in the epidemic phase. Write your answers down.

As noted earlier, volunteers can play many valuable roles during an epidemic because they live in or know their local communities.

Always remember, however, that you are not the only ones helping people. Staff in the Ministry of Health, and the doctors, nurses and health workers in health facilities, do vital jobs. Other organizations may also be working in your community and helping to manage the epidemic. It is very important to coordinate with all of them and work together in a way that benefits as many people as possible.

We will talk now about the general actions that need to be taken in all epidemics. Afterwards, we will look at specific actions that need to be taken to manage specific diseases. These will be discussed more fully when you learn how to use the toolkit.

In all epidemics, you need to:

- Make yourself familiar with the epidemic response plan. Start to follow it as soon as the epidemic has been confirmed and the plan has been activated.

- Coordinate closely with health authorities.

- Ask to participate in refresher training, if this has not been done in the alert phase.

- Start using the toolkit attached to this training manual. Assemble your toolkit for the epidemic in question, check to make sure that official guidelines have not changed, and start using it.

- Start using the resources that were stocked during the preparedness and alert phases.

- Initiate active surveillance in coordination with the health authorities. Start detecting cases in the community and referring them to health centres as required.

- Make yourself familiar with the referral system and follow it.

- Follow cases up by making house visits and filling in registration forms.

- Carry out health promotion activities in affected and at-risk communities.

- Take prevention actions that are appropriate for the disease in question.

- Keep in touch with local health workers, community health workers and midwives.

- Participate in prevention and response actions by the health authorities and other partners (health promotion, mass vaccination campaigns, action to improve water and sanitation, etc.).

- Provide psychosocial support to people in the community, volunteers and staff.

- In some epidemics, when instructed by health professionals, trace and find the contacts of sick people who might carry the disease or fall sick themselves.

- Familiarize yourself with the safety measures that are appropriate for the disease you are dealing with and observe them (1.2.4).

Part 3.3.2. Social mobilization, behaviour change communication and community engagement

Mobilizing communities and helping them to adopt safer, less risky behaviour is critical during an epidemic. Safe behaviour might include agreeing to be vaccinated, washing hands with soap at the five critical times, regularly wearing mosquito repellent, consistently using a mosquito net, or agreeing to be isolated from others while sick.

| Social mobilization |

|---|

| includes any activity that assists members of a community to take action to protect themselves, reduce risks, and prevent diseases from affecting them and spreading to others. |

| Behaviour change communication (BCC) |

|---|

| identifies and uses trusted communication channels to deliver information designed to change behaviour. |

| Community engagement |

|---|

| uses a variety of communication approaches (including theatre) and trusted media (such as local radio) to reach, influence, and involve communities by providing accurate, easily understood and trusted health information about a disease. It sets up systems for listening to communities, gathers feedback, and counters misinformation and rumours, in support of efforts to change behaviour and deliver services. |

Behaviour change in epidemics

Development programmes like CBHFA use evidence-based health promotion activities to create sustained, long-term behaviour change. Behaviour change models need to be adapted for epidemics because these occur and evolve swiftly and programmes need to be scaled up fast. Research has shown that people can change their behaviour in emergencies for approximately six weeks. After this time, they tend to fall back into their old behaviour unless risks continue to be communicated well and their work and home environments support behaviour change. A risk is communicated well when health teams consistently identify health risks linked to social and cultural norms and continue to monitor communication between the Red Cross Red Crescent and the community to ensure that efforts to change behaviour remain appropriate and effective as the crisis evolves.

In an epidemic, the aim is to develop a strategy for working with the community that quickly changes risky behaviour and stops the disease from spreading. The goal is to change behaviour for as long as the risk of disease is higher than normal. The longer term goal is to create healthier communities by eliminating risky forms of behaviour altogether – to change behaviour not just during the epidemic, but afterwards too, because this will make epidemics less likely in the future. For more information, see the behaviour change module in eCBHFA.

Response teams often simply provide information about the risks associated with certain behaviour. We need to remember, however, that people do not tend to change their behaviour as a result of receiving information. According to the transtheoretical model, there are five stages of behaviour change – even in an emergency. In normal times, people progress through these steps slowly, but in an emergency they can go more quickly, especially when they see the effects of the epidemic all around them.

Figure 10. Five stages of behaviour change

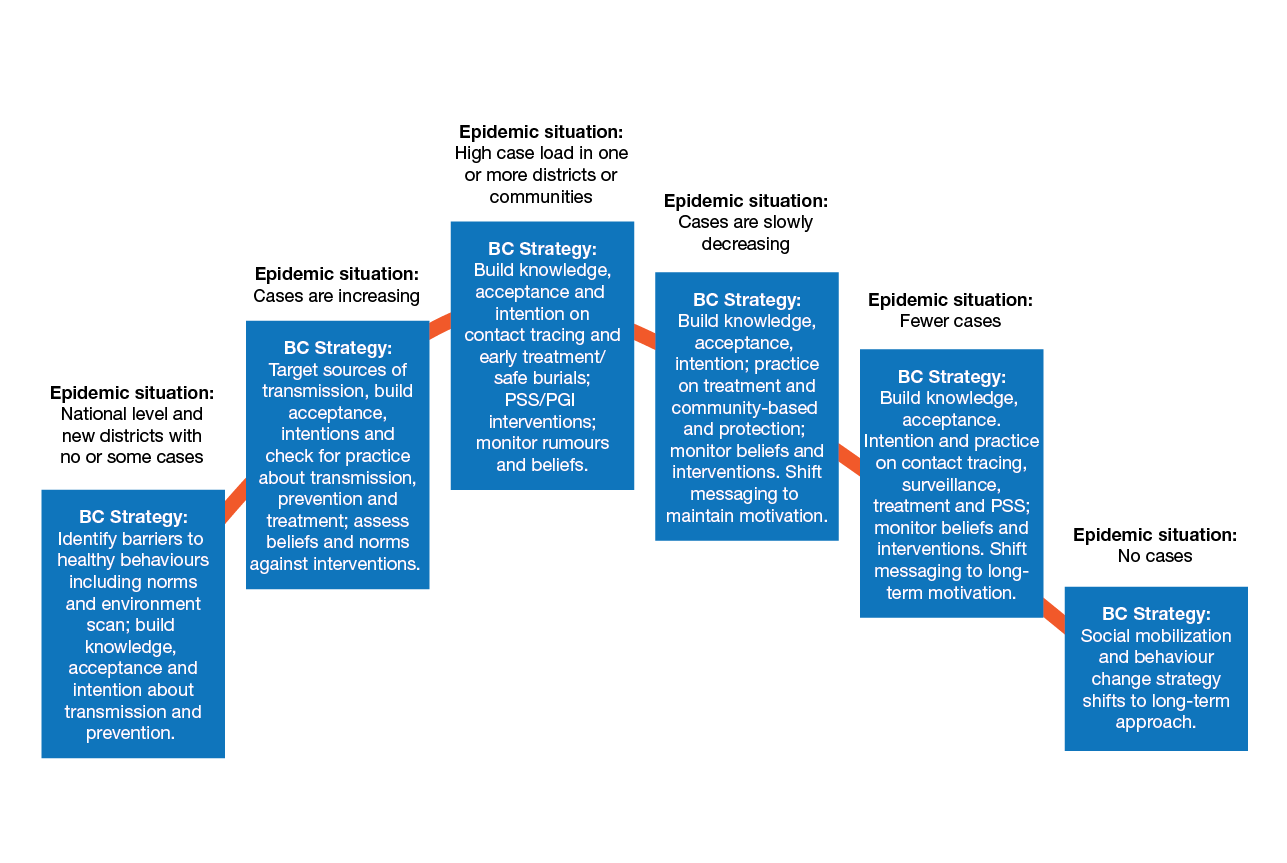

In an epidemic, a person’s behaviour is determined by knowledge, but also by whether he or she thinks the disease is serious or thinks he or she is likely to fall sick; by the benefits or disadvantages of changing behaviour; and by social norms, cultural practices and beliefs. Some barriers – such as fear, mistrust and confusion - are difficult for a person to overcome. All these aspects must be considered when identifying a behaviour change strategy in an epidemic. See Figure 11 below, which shows the arc of an epidemic and how a behaviour change strategy alters at each stage. Note that it is important to keep communities informed and to monitor beliefs throughout because public reactions evolve as an epidemic progresses.

Figure 11. Behavioural change in epidemics

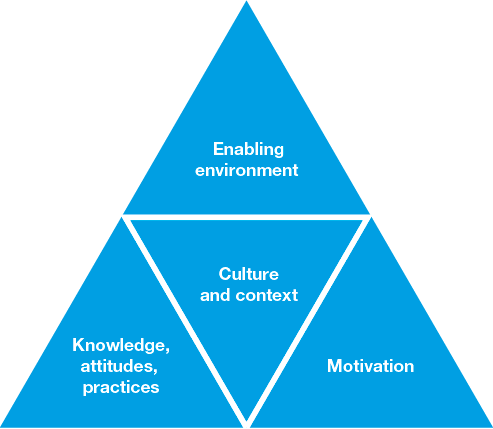

Figure 12. Behaviour change triangle

In any context, three elements are involved in behaviour change:

- People need to know what in their behaviour needs to change, why it needs to change, and how to change it. In other words, they need knowledge.

- People need access to the right equipment and resources, and to be in a position to change their behaviour. They need an enabling environment.

- They need to be motivated to change.

Each of these factors is influenced by culture, social context, perceptions and beliefs. It is the balance between these factors that determines whether people will change their behaviour or not. In a development context, people do not typically respond to fear-inducing messages, such as the one below, which encourages people to wash their hands.

Figure 13. Cholera poster

In a cholera epidemic, by contrast, this type of message might be very effective, because people will already be aware that they are at risk and will be receptive to fear-based messages.

To see how people move from one stage to the next in behaviour change, look at the eCBHFA module on Behaviour change.

How to identify barriers to change

Barriers that prevent people from adopting healthy forms of behaviour include people, rules, norms and environmental factors. To give your behaviour change strategy a chance of success:

- Find out what people in the community currently know and believe about the proposed healthy behaviour.

- Find out how people in the community currently behave and why they behave as they do.

- Do an environmental scan in the affected community to find out what factors contribute to unhealthy behaviour. An environmental scan assesses the physical environment to identify actors, institutions, policies, rules and programmes to prevent and treat disease. For example, in a cholera epidemic, you might interview people who provide water or who access a community water source to find out how they draw and use water, where local water sources are, whether the source of water is safe, and what policies or rules govern water distribution and use.

Barriers to behaviour change

Social mobilization or behaviour change communication may be ineffective for a number of reasons. For example, the people you want to influence may:

- Distrust the person who communicates the information.

- Hold different beliefs or disagree with the content of the message. (They may consider, for instance, that it conflicts with traditional beliefs or common social practices in the community.)

- Desire to change but lack resources to do so. (For instance, they may want to wash their hands but have little water or lack soap.) People may also be unable to reach health centres.

- Lack support from those around them (including family and influential people in the community such as religious leaders, traditional healers, midwives, business leaders, politicians, etc.).

- Consider that changing their risky behaviour is not a priority because they have more urgent interests or needs.

- Be unable to change their behaviour without community approval or unless all members of the community agree to change.

Communicating with communities in epidemics

Clear, trustworthy and effective communication is very important during an epidemic. But it can be difficult to achieve. Providing information to communities is rarely enough to change peoples’ behaviour. Fear, grief, cultural beliefs, traditional practices and misinformation can all make effective communication difficult.

| Community engagement is a core principle of long-term health programmes (including CBHFA) as well as epidemic control. For guidance and tools, see CEA guidance. |

|---|

Communities may not trust the authorities or the health system, with the result that information about a disease or about how to control it is misunderstood or taken to mean something else. Strong belief in traditional medicines, lack of understanding of how diseases are transmitted, or unwillingness to accept treatment (including vaccines), can complicate things further.

For these reasons, any communication designed to mobilize people or change their behaviour in an epidemic must put the community at the centre and work with the community to identify solutions.

In an epidemic, you should aim to achieve two-way communication with communities. As volunteers, you are in daily contact with leaders and members of the community. Talk to them about their perceptions and fears, how they think the disease is transmitted, what motivates them to change their behaviour, and what stops them from changing. Listen hard to what they say.

Remember that “sensitization” tends to describe one-way communication; it is about giving information. “Mobilization” is more about communities taking action, and usually implies two- way communication.

To mobilize communities effectively, and change behaviour successfully, communications should respect certain guidelines.

Communications should be:

- Simple and short. Messages should be easy to understand and repeated frequently.

- Delivered by individuals or media that people in the community trust.

- Specific and accurate.

- Consistent. Remember to make sure that other community workers, agencies or organizations are not issuing messages that contradict yours. This will confuse the community.

- Action-oriented. Messages should make clear what people should do. Focus on actions that community members should take; avoid giving lots of information that does not trigger action.

- Realistic and feasible. People must be able to do what the message recommends.

- Sensitive to context. Messages should take into account social and cultural attitudes or customs that influence the readiness of members of the community to adopt safe behaviour or accept treatment (such as vaccinations).

When you communicate with a community, always listen for rumours or misunderstandings that might be spreading. Rumours can generate panic and fear. They can also cause communities to distrust health authorities, doubt their effectiveness, or reject interventions that will prevent the spread of disease.

How do we communicate?

There are many ways to spread information, build knowledge, and promote action in communities affected by epidemics. Some are described in the table below.

Table 3. Commonly used communication channels

| One-way communication | Two-way communication | Participatory methods |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Can you think of other ways to communicate?

Illustration 3. Face-to-face communication

Illustration 4. Volunteer promotes health at school

Illustration 5. Talking to the media

Volunteer actions in the community

As a volunteer you will talk to community members about risky practices and help them to adopt safer behaviour that will stop the epidemic from spreading and prevent them from getting sick. It is equally important to listen to what the community tells you. Let your supervisor know if you hear rumours or incorrect information or the community says that an activity is inappropriate or offends cultural or social practices.

In the toolkit, you will find community message tools that can help you communicate the right messages to the community. But remember, they must be adapted to your community and your context: this is your responsibility!

As a volunteer. you should also be a “model” of safe behaviour for others. As you go about your day-to-day volunteer activities, make sure you wash your hands, follow coughing etiquette, etc.

In addition, you should:

- Familiarize yourself with the community’s cultural beliefs, about health, about the disease that is of concern, about caring for people who are sick, accessing health care services, etc.

- Find out what messages are being communicated by other groups in the community (including community leaders and other organizations working in the same area).

- Discuss behaviour change messages with coaches or supervisors, community leaders, health workers and other volunteers, to obtain their insights and input.

- Work with families, communities, authorities and health services to influence social norms.

- Use simple and clear messages in language that is easy to understand.

- Communicate your messages in different ways; make sure that community members can summarize them accurately.

- Listen actively, including for rumours or incorrect information.

Group work and role-play

Divide into groups. Each group will look at messages taken from community message tools.

Discuss these messages and the appropriateness of the tool for your own communities. In a brief role-play, show how and through what media (e.g. face-to face, group session, radio, play etc.) you would deliver the messages in your community.

Part 3.3.3. Referral

People sometimes become very sick, and volunteers cannot provide the support they need. Those people need professional care by nurses and doctors. As a Red Cross Red Crescent volunteer, you do not generally provide medical care (with the exception of first aid and ORS. But you can identify cases and help people who are sick to reach medical professionals and health facilities.

You will find sick people through active community-based surveillance. Before you refer them to health facilities, you need to know how sick they are and whether they need referral. You can do this by using the toolkit and the descriptions you have of each disease.

You also need to know all the health facilities near you (hospitals, clinics, health centres, cholera treatment facilities, etc.), how to reach them, and their admission criteria. In order to limit transmission, the health authorities may sometimes decide that one health facility should receive all epidemic referrals.

You may need to take the patient to the medical facility. You should be able to tell people where they are located.

When you refer people to health facilities, make sure you do not put yourself or other people at increased risk of transmission. Check the personal protective equipment (PPE) needs for each disease.

Part 3.3.4. Different roles and coordination

It is important for volunteers to organize themselves in a way that allows them to help as many people in their communities as possible, while delivering health messages effectively.

How do we coordinate?

- Talk to your local Red Cross Red Crescent branch and to health authorities. Find out what they are doing to organize themselves and how they plan to help the community. Understand your role and how you can assist.

- Make a plan. Decide consultatively who will cover what activities in which locations.

- Communicate with other volunteers. Meet at least once a week to update each other on what has been done to help the community and what needs to be done next. Share lessons and support one another.

- Talk to your facilitator and discuss additional ways in which you can work together.